SALIDmag 09.21.2025

FALL 2025 ISSUE

Welcome to the second issue of SALIDmag (South Asian Languages, Images, and Data Magazine), published on September 21, 2025. We hope you enjoy reading the second issue. This issue of SALIDmag has a feature article, a book review, and two readers' essays on novels in South Asian languages other than English.

General Editor Sheenjini Ghosh and Book Review Editor Ragini Chakraborty are both graduate students of Comparative Literature. Feel free to write to them (scroll down the page for their emails) with comments on the current issue or about story ideas for the Spring 2026 issue.

A MESSAGE from the General Editor and the Book Review Editor

When we first envisioned SALIDmag, we imagined a space where scholarship, storytelling, and community could meet. To welcome our second issue in Fall, after the inaugural Spring 2025 volume, is humbling and heartening. The journey so far has been inspiring, and for us, a deep learning experience as editors.

Our first issue was in Spring 2025, and it featured a feature article on artist Sumit Kumar's world of comics and visual storytelling. It also included a “novel” experience submission focused on a Kannada novel and a review of a recent publication on the intersection of performances and narrative spaces through a reading of Karbala.

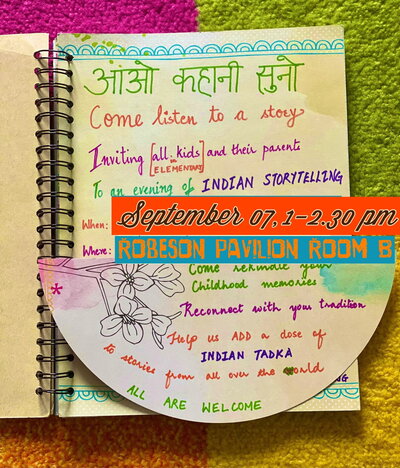

Our second issue in Fall 2025 attempts to continue celebrating South Asian academic and cultural endeavors at SAS Initiative at UIUC. From a feature on Aao Kahani Suno and its community of stories to a review on mapping the scope of translation in India to “novel” experiences that bring Bengali literature into sharp focus, each contribution extends our conversation across languages, histories, and lived realities.

As the General Editor (Sheenjini Ghosh) and the Book Review Editor (Ragini Chakraborty), working alongside each other has been a privilege. Our contributors' and collaborators' rigor and generosity have shaped our magazine issues so far.. With each call, more voices reach out to us, and I look forward to seeing SALIDmag grow in numbers and depth. Our hope is that future issues continue to carry forward this spirit of inquiry and belonging.

Sheenjini Ghosh & Ragini Chakraborty

FEATURE ARTICLE: Stories, Clay, and Community (Sheenjini Ghosh In Conversation with Divvya A. Singh)

On a Saturday afternoon in Urbana-Champaign, the quiet of a public library gives way to children’s laughter. Small hands roll clay into familiar shapes from home, sometimes a Ganesha, sometimes something else imagined on the spot. Others cut patterns in bright paper, while a voice rises above the busy hum. Walking among them, a book in hand, is Divvya A. Singh, a reader, poet, volunteer, and founder of Aao Kahani Suno (AKS). Twice a month, she transforms an ordinary library room into a space where children encounter the heritage of South Asia through stories, rituals, and creative practices that might otherwise slip from reach. Besides Aao Kahani Suno (AKS), Divvya has also taken up the initiative to host a day of celebrating a South Asian-style fair filled with nostalgia, childhood memories, fun, and games, which she likes to call the Mela.

A banker by training, a mother by choice, and a community-builder by conviction, Divvya began Aao Kahani Suno (AKS) in 2024, inspired by the simple act of reading stories to her child and recognizing the need for a space where such moments could be built into a community. What began as an initiative in May 2024, has, in just over a year, grown into intimate storytelling sessions and a vibrant community festival like Mela: Bachpan Unfiltered, which was held in August 2025 at the Asian American Cultural Center, UIUC.

In this conversation for SALIDmag, Divvya reflects on her journey, the sensitive work of cultural preservation, and the joy of watching children light up with recognition.

SALIDmag: Children often surprise us in the ways they absorb tradition. At Aao Kahani Suno (AKS) and during Mela, you’ve seen them chant, craft, and listen with striking intensity. Could you share a moment that affirmed your vision, when you felt a cultural connection truly take root?

Divvya: It is deeply gratifying when children ask questions they have been quietly pondering, and I get to witness the spark of understanding light up their faces. One moment that stands out was after our Ganesha event, when a parent shared that their child had become so enamored with the chant that they wanted to play it again and again. It was a quiet affirmation that we were building the connection we had hoped for.

SALIDmag: Building such a platform in the diasporic community means balancing preservation with adaptation. You cannot simply replicate tradition; you must translate it for a new context. How do you choose which stories to tell and which rituals to emphasize, so they remain meaningful for children growing up here?

Divvya: Preservation lies at the heart of what I do. So much of our cultural memory, our stories, our rituals, can fade when we move away from the homeland that nurtured them. In India, we absorbed these traditions instinctively. Here, we are asked to explain them, and in doing so, we rediscover their meaning.

I usually bring stories I carried from India or borrow books by Indian authors from the library. The choice is intentional, so children encounter familiar characters, words, and rituals that feel their own. Sometimes though, I include stories about immigrant characters, they see themselves mirrored in the page, they feel represented and understood.

SALIDmag: Your sessions are not limited to reading. They invite children to make modaks, shape clay Ganeshas, or craft as they listen. That tactile, sensory engagement seems as central as the story itself. What does this pairing of activity and narrative achieve for children that reading alone cannot?

Divvya: Anything we experience through a creative process stays with us. It engages more of our senses, it’s not passive, it’s participatory. When children create something, it becomes an extension of themselves. That pride, that ownership, helps them connect with the deeper significance of their work. Kids don’t respond well to lectures. What truly matters becomes meaningful when it’s interactive.

At times, I hand out crafts so children can work with their hands while I walk around reading stories aloud. Their attention flows differently: they are both listening and creating, both rooted and free.

SALIDmag: You are trained in Economics, worked in the banking industry, and organized cultural events even then. But here, away from extended family and familiar networks, you’ve built something entirely new. How has that transition, from banker to community storyteller, shaped your sense of purpose?

Divvya: Creativity has always been a part of me, even in my banking days, when I organized Diwali events and cultural gatherings. My training taught me how to manage resources carefully, and that has helped here. When I began Aao Kahani Suno (AKS) in May 2024, I conducted the first sessions out of my own savings, simply hoping to plant seeds of cultural growth. I may not always know what those seeds will grow into, but I see the joy on children’s faces, the friendships they form, the ease with which they connect with ideas, and that gives me peace. It fuels my desire to keep going.

That journey was further enriched by the South Asian Studies Initiative, which really gave me the wings to try something bigger, like Mela. Just as important has been the steady encouragement of my dear friend Manjula Tekal, who has stood by me from the very beginning. Without that mix of academic support and personal friendship, I don’t think Aao Kahani Suno (AKS) would have grown the way it has.

SALIDmag: At the library, you see children listening, but also parents hovering, grandparents quietly observing. What role do families play in sustaining this circle once the sessions are over?

Divvya: I get to see the children because their parents choose to bring them, again and again. Their commitment and belief in what we’re doing are what bring me back every fortnight. Aao Kahani Suno (AKS) thrives because of its community. Ours is a community that values shared experiences, that finds joy in collective learning. AKS may have offered the platform, but it’s the parents’ consistent effort to give their children a cultural foundation that has kept it alive.

SALIDmag: Diasporic children often inherit culture in fragments: a ritual remembered, a festival celebrated halfway, a story retold in pieces. How do you use storytelling to weave those fragments into something more cohesive?

Divvya: I started Aao Kahani Suno (AKS) to address the schism many of us feel, to offer a space for cultural representation and reconnection. When we understand our roots, we grow stronger. This isn’t about enforcing tradition; it’s about sharing our stories. My goal is to help children build a collective identity that includes finding their own voice so they can discover themselves. Because how can we truly know ourselves if we don’t know where we come from?

SALIDmag: Screens compete relentlessly for children’s attention, reels, shorts, and games promising instant gratification. Yet twice a month in Urbana, children sit still to listen, craft, and question. Why do you think oral storytelling still resonates so powerfully, perhaps even more so in the diaspora?

Divvya: Humans respond most deeply to connection. In live storytelling, there’s an exchange of energy between the teller and the listener. The storyteller adapts in real time, sensing what resonates. The listener, in turn, feels seen, heard, and empowered to share their own story. This fosters empathy, understanding, and a sense of belonging.

To me, oral storytelling is like teaching your child to cook, hands-on, sensory, and memorable. Digital entertainment, by contrast, is like opening a box of pre-made food. It may satisfy momentarily, but it doesn’t nourish connection.

SALIDmag: Do you see Aao Kahani Suno (AKS) and Mela evolving into more intergenerational spaces?

Divvya: Absolutely. We’ve already celebrated Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, and Grandparents’ Day with shared crafts and stories, weaving together generations. We strive to be a bridge between East and West, honoring the wisdom that has shaped us. That wisdom, passed down and reimagined, becomes the foundation for resilience in our children, especially those growing up in the diaspora.

Listening to Divvya, it becomes clear that Aao Kahani Suno (AKS) is not just a set of library sessions or a fortnight get-together; it is a practice of community-making. Twice a month, a handful of children leave with crafts tucked under their arms, clay on their fingers, chants on their lips. Parents bring them back, grandparents join in, and friends step forward to sustain the work. In these circles, stories are not just preserved; they are lived.

What Divvya has built, in essence, is a living archive of belonging. In Urbana-Champaign, far from the rhythms of joint-family life, she has created something both fragile and enduring: a reminder that identity, like clay in a child’s hand, is shaped through stories shared aloud. And perhaps the future will see these circles expand, more children, more stories, more hands shaping clay and memory together. For now, each gathering is proof, that a community can find its root anywhere, and that the seeds of belonging, once planted, will grow.

BOOK REVIEW: Kabir Deb reviews Rita Kothari (Ed.) 'A Multilingual Nation: Translation and Language Dynamic in India'

MANY TONGUES, MANY TANTRUMS: A VOICE BEYOND SINGULARITY

Book: A Multilingual Nation: Translation and Language Dynamic in India. Edited by Rita Kothari. Published by: Oxford University Press, 2018, India. 376 pp.

Review by: Kabir Deb

The idea of a good translation comes from an understanding of the significance of languages and their association with people. Moving between languages is tethered to people's everyday life in a country like India. It exists in the presence of hunger. It blooms even around death. It grows both in the company of innocence and greed. The multilingualism of India makes the process and works of translation in Indian academia challenging and complex. The change in the dynamics of a language throughout its journey has been responsible for changes in the process and objective of translation and translators. In the pool of translation, translators are not just creating something from a source. Rather, they are experiencing the source to let it flow using their words. At the end of the entire process, what is reincarnated is a new origin.

A Multilingual Nation: Translation and Language Dynamic in India, edited by Rita Kothari, is an attempt to expand the world of translation for readers engaged in understanding, exploring, and experiencing translational works. The editor asks a significant question through this book: Is translation a projection of various languages, or does it establish one universal language? The book helps us to see how languages are connected, a truth we especially recognize when we read literature in translation and realize that more than one language can live within our mind simultaneously.

Translation also brings a certain kind of disbelief towards glorifying one language in the form of a mother tongue. In the present time, when ethnic clashes happen because of linguistic differences, translation helps people understand the singularity of an idea when people speak different languages. Thoughts do not vary. Translation clarifies how, in personal lives, we behave and think similarly. This anthology brings together translators to speak about a multilingual nation and how they manifest and implement their skills to bring before readers a readable document. The variety of languages spoken or written does not mitigate, but the difference between them does.

In her essay “When a Text is a Song”, Linda Hess writes about Kabir, what she understands about his words, and how significant he is for anyone interested in translation. Kabir never wrote a single poem (Doha) on paper or leaves, so the eyes cannot trace what he said about the country's brutal reality and structured communities. For this reason, sound and rhythm became the primary components of her research. Hess says that, in the case of translation, the entire body works when a translator begins translating a project. One has to be mobile since the original words are not static. They flow to give a new meaning every time we go through the project. In the initial part of her exploration, she found Stanley Fish's theory of audience-response as the key to translating Kabir. People have been the main element of Kabir's poetry. Hess understood that to do good work, she has to address the audience, who have listened to Kabir more than reading him in books. The same goes for Sant Tulsidas, Lalon Fakir, and various other oral storytellers of India.

In this essay, Hess points out that under any circumstance, nothing can be considered an authority or a standard source to understand and translate Kabir. Even in the oral system, Kabir has used similar poems to address different situations and different poems to address similar situations. The poet cannot be standardized, and even Hess knows that her projects cannot be taken as canonical for all readers. Thus, in the essay, she asks an important question: Were other people experiencing the text the way she was, or differently? Translators have the responsibility of translating a text without maligning its familiarity, relevance, and relatability. Unless a translation manages to hold the readers, the awards and glory do not mean anything since the first subject that a book acknowledges is society. Kabir's oral and musical projection of his thoughts becomes a setback if one does not attend to the sound, rhyming, and rhythm. Also, we cannot maintain distance from those who have collected Kabir's work in their books since they proliferate thoughts.

On her journey to explore Kabir, Hess had to move to different parts of the country to listen to people who preach him consciously or unconsciously. This journey especially nurtured an axiom in Hess' mind: to know Kabir, you should know people. Kabir was an experiential poet. He used to sing what unfolded before his eyes. It would not be wrong to say that Kabir would have had very little significance in an absolute society. He is still significant because he is the voice of the voiceless. His ideas came out of idealism, and they exist inside everyone. The relevance of his poems is not surprising at all. Hess puts before us one of the techniques through which the poet can be translated. This is certainly not the only template, but it gives translators good clarity.

Rita Kothari, in her essay Grierson's Linguistic Survey of India: Acts of Naming and Translating, speaks about the first and largest documentation of languages in India, which was undertaken by G.A. Grierson. In the first part of the essay, Kothari mentions how schools have been neglecting multilingualism, since most of the time, these structured institutions of language serve as insurance. They provide education to help students get a good job. The proficiency of language mostly happens outside the classroom, but with a lot of pride attached to a medium of communication. It is for this reason that in many parts of the country, we see division of a single language based on caste. Human voice is a weapon. Control can be best established by hijacking the basics of a human being's voice. From Alexander to the British, language was the first strike.

Translation in India has always been done with a humanist attitude. Those that are done entirely based on profit and fame, without any human connection with the original language, turn out to be mediocre projects. Kothari mentions that it is solely done because the languages of India are not spatially arranged isomorphs (isomorph is a structural mapping which can be inversed whenever needed). In case of language, Hindi and Urdu are isomorphs just like Tamil and Malayalam. They have their own differences, but if seen from a close distance, they are inverted reflections of each other. Kothari's essay questions the non-existence of the demarcation of languages. It is not a spiteful question. Rather, she knows that due to the absence of barriers, languages quietly blend. But then, we create our own barriers to fulfill our linguistic existence.

Colonization led to the influx of a foreign language in our land, and as we know, they made their own language the official one, to ensure the Indian clerks could solve their problems. In an interesting move, G.A. Grierson, during his survey, documented 179 languages and 544 dialects by covering 224 million Indians out of 300 million. It was a commendable effort, and even today, his book guides translators to understand the languages that are cultivating and evolving in India. The Brahmins made Sanskrit exclusive and holy but forced others to take it as a necessary medium, which led to the exclusion of other languages. After his survey, Grierson issued scholarships for various other languages since he saw that monetary benefits were being given to only those students who were well-versed in Sanskrit. The Parable of the Prodigal Son and folklore taken from the mouth of the speaker acted as two elements that can help various scholars translate what they are not familiar with into the language they speak, read, and write. This became one of the first moves in colonial India towards translation.

Grierson faced several difficulties while translating a mainstream text in India. One of the significant difficulties, which is still prevalent, stems from the alienness of an individual towards his own language. Many people in India are still unaware of their spoken language since childhood. Even then, Grierson's survey showed translators a way to make several languages of India reach the mainstream. Like Kothari says in her essay, translation in India is a nationalist move since translators are bridging gaps and ensuring every language gets universality without losing its originality. It is a step towards identifying the uniqueness and opportunities in our nation.

Mitra Phukan, in her essay When India's North-East is Translated into English, keeps a vital gift and lists the problems that the translators of India must endure. Phukan, being an Assamese, says that Assamese influences her English (both spoken and written). Many might consider it a move where the translator has not shed her skin to present an absolute translation. But how is it even possible for translators to revoke a language they have been speaking since childhood from their minds? Translators who carry a tinge of their mother tongue while translating ensure that readers understand that quality in their absolute works, a slice of their origin.

She also points out that if a person's first language differs from their mother tongue, they will influence each other. This is not restricted to speech. The same happens in the case of writing. However, translators and their works do not codify the influence of one language over the other. Phukan herself says that her source language, Assamese, greatly influences her work of English fiction. But with time, new-age writers and translators have forgotten the actual pronunciation of a word in the original language. It has become a debate between history and phonetics. The root will go towards history. The branches will not.

Translating from multiple tongues comes with certain responsibilities. The primary being care, where translators need to understand that every language has its own mapping and conditioning. No one can spoil that map because India's culture lives in its languages. The politics of Assam is not all merry. The conflict among multiple languages has restricted people from translating them. A certain sense of sensibility is what Phukan addresses in the last part of her essay. Translation covers a bigger ground with just a single worker.

A Multilingual Nation: Translation and Language Dynamic in India is a profound book that every translator should go through to understand what they need to do in the presence of multiple languages. Translation is not a job or profession. It is an exhaustive work with a fruit that decides the fate of every nation's literature. From Germany to Japan, translators have unified people who study and explore stories. In the case of India, language is a delicate and sensitive subject, and to make stories penetrate every home, irrespective of any social prejudice, one must take translation as a healing process. In times of linguistic division, translators are physicians. They exchange words and refer to both the past and the present to let the result keep people in peace and comfort.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

Kabir Deb is a writer based in Karimganj, Assam. He is the recipient of Social Journalism Award, 2017; Reuel International Award for Best Upcoming poet, 2019; Nissim International Award, 2021 for Excellence in Literature for his book Irrfan: His Life, Philosophy and Shades. He reviews books, many of which have been published in national and international magazines. His last book, The Biography of The Bloodless Battles, was shortlisted for Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar, 2025 and Muse India Young Writer's Award, 2024. He works as the Interview Editor for the Usawa Literary Review.

AUTHOR'S INFORMATION

Kabir Deb. Email: ratedr.mondeep58@gmail.com.

A NOVEL EXPERIENCE: Aishi Bhattacharya on Tilottama Majumdar's 'Rājpat'

Title of the novel: Rājpat

Author: Tilottama Majumdar

Original language: Bengali

Year of publication: 2019

Tilottama Majumdar's Rajpat is a vast, layered Bengali novel that unfolds at the crossroads of history, geography, spirituality, and politics. Rooted in Murshidabad, a region shaped by the restless currents of the Ganga, the novel draws as much from the river's rhythms as from human conflict. The Ganga here is more than a backdrop; it is a living force, its floods and erosions pressing upon people's lives with as much weight as social hierarchies or political power.

At the heart of the novel stands Moyna Vaishnavi, a woman whose spiritual devotion is shaken when she uncovers a human trafficking ring under the garb of an ashram. This discovery comes as a blow to her faith and compels her to confront a disturbing truth: that institutions claiming sanctity can also become vehicles of violence and exploitation. Moyna's journey reflects the uneasy tension between faith and power, between the sacred and the profane. Parallel to her story is Siddhartha Bandopadhyay, a figure of political integrity whose commitment to justice underscores the need for systemic resistance.

While Moyna's struggle is inward—an awakening that forces her to rethink belief, Siddhartha's is outward, a call for collective action. Together, they represent two necessary currents: personal courage and social struggle, both essential for dismantling entrenched exploitation.

Rajpat also draws deeply on Bengal's literary tradition of tying human lives to the flow of rivers. By locating its story in Murshidabad, Majumdar reminds us that geography is never passive; it actively shapes history, belief, and ethics. The critique of an ashram masking human trafficking extends beyond a local scandal. It becomes a meditation on how spiritual discourse can be weaponized to justify violence. This theme resonates far beyond Bengal and touches on global anxieties about the misuse of religious authority. What makes Rajpat compelling is its refusal to flatten these tensions into a neat moral lesson. Majumdar's prose asks for time and immersion; its density mirrors the weight of the themes it takes on. The novel insists that the reader sit with discomfort, just as its characters must. Rajpat is a significant contribution to contemporary Bengali literature in scope and depth. It critiques exploitation while also offering a vision of resilience. For readers outside Bengal, it provides an entry point into South Asia's intertwined histories of land, faith, and politics, while posing urgent universal questions about violence, belief, and resistance.

Personal Reflection

Reading Rajpat was not easy. It is a demanding novel, heavy in both length and theme. At first, I found the vastness almost overwhelming. But slowly, I began to see how that also about the universal entanglement of power and faith. For me, Rajpat was less about reaching a conclusion than about sitting with questions—questions that continue to linger after I finish it. The novel reminded me that resistance is not an abstract ideal; it is something lived, often quietlyimmensity was part of its power. The novel flows like the Ganga itself: restless, inexhaustible, sometimes devastating. Moyna's journey moved me most, from devotion to disillusionment to a redefined sense of resistance. Her story made me pause and think about the institutions we take for granted and how they can harbor shelter and danger.

I realized that Majumdar was not only writing about Murshidabad or Bengal but about the universal entanglement of power and faith. For me, Rajpat was less about reaching a conclusion than about sitting with questions—questions that continue to linger after finishing it. The novel reminded me that resistance is not an abstract ideal; it is something lived, often quietly, but always urgently.

Links related to the Novel:

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/21570166

Wikipedia (Tilottama Majumdar): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tilottama_Majumdar

Ananda Publishers (official site): https://www.anandapublishers.in/

A NOVEL EXPERIENCE: Rituparna Mukherjee on 'Bireshwar Samantar Hatya Rahasya' (Who Killed Bireshwar Samanta?)

Title of the novel: Bireshwar Samantar Hatya Rahasya

Author: Sakyajit Bhattacharya

Original language: Bengali

Year of publication: 2024

One of the priests in Spotlight (2015), directed by Tom McCarthy, highlights faith's institutionalized nature when he says, "Knowledge is one thing, but faith, faith is another." This dichotomy between knowledge and faith demonstrates how power sustains itself in society through an unholy nexus between state and civic bodies, while common people bear the burden of its hegemony. This Gramscian understanding of power is explored truthfully in Sakyajit Bhattacharya's Bengali novel, Bireshwar Samantar Hatya Rahasya (Who Killed Bireshwar Samanta?), which appears to be a crime novel at first glance but is also a deep reflection on rural land politics, violence, class and caste issues, patriarchy, and, above all, a philosophical interpretation of revenge.

Temporally, the entire novel spans a single day. The villagers discover the body of the village patriarch, Bireshwar Samanta, hanging from a tree. Everyone in the village knows who killed him and why. A crowd gathers at the scene, along with police and political leaders. The narrative then delves into history, exploring seventy-five years of events to uncover why Bireshwar Samanta was murdered. In this process, six key characters emerge, and the novel is divided into six chapters, each corresponding to a character, with a prologue and an epilogue. These chapters are presented through their voices, giving readers six perspectives from which to view the same event. The layers of the mystery unfold through their thoughts and perspectives, constructing history as a living, pulsating organism, birthed in the violence of both masters and subalterns alike. The novel takes an insightful look at the ever-present human proclivity for violence and exploitation.

The first chapter, "Bireshwar Samanta," introduces the village, Ananta Bhumi, the history of the Samanta family, and Bireshwar's spectacular rise to power. The story then shifts seventy-five years back to focus on Bireshwar's father, Jogeshwar, their servant Bhisma Bagal, and Bhisma's wife, Saptami. This episode examines the nature of power between masters and servants and glimpses the place of women in a severely patriarchal setup. Jogeshwar makes Saptami his mistress, but not entirely by force. Saptami is also drawn to her master and to the power this relationship provides her. Soon she is pregnant, and although the child is named a Bagal, there is little doubt about the child's paternity. Feeling betrayed, Bhisma joins the Tebhaga movement and is caught and killed. He vows revenge, as does Saptami, which becomes regional lore—that the Bagal blood will eventually seek reparations. This murder seems to fulfill that mythical vow.

The second chapter, "Nakul Katal," presents the perspective of a local communist party worker who reminisces about his past conflicts with Bireshwar Samanta over land rights.

The most compelling chapter, the third, is narrated by Saptami, now 98 years old and bedridden. Saptami recalls how her son, Bhim Bagal, was arrested and tortured to death by police during the Emergency period, orchestrated by Bireshwar. The villagers believed Bireshwar was killed because of rumors that he had impregnated her great-granddaughter, Rohini. However, Saptami reveals that she had spread the rumor vengefully, without knowing the actual culprit's identity.

The fourth chapter, "Poltu," is narrated by its namesake, Poltu, a loyal companion of Debu Bagal. Together, he and Debu planned and executed Bireshwar's murder. This chapter focuses on the murder itself, describing how the duo killed Bireshwar and how the entire village aided them. Through Poltu's memories, we learn how Debu—Saptami's grandson and once a timid worker under Bireshwar—ultimately gathered the courage to carry out the murder.

The final two chapters, "Rohini" and "Sarbeshwar," present the perspectives of the latest generation standing at opposite poles of power. Someone from the Samanta household rapes Rohini, but it is not clearly stated whether it is Bireshwar or his son, Sarbeshwar. In the final chapter, Sarbeshwar reflects on how he manipulated Debu into murdering his own father. Although the novel hints at a relationship between Sarbeshwar and Rohini at this point, it doesn't clearly specify this connection, alluding to the erasure such relationships usually face. The novel thus intricately weaves a narrative of history, politics, and personal vendettas, leaving readers with lingering questions and unresolved mysteries.

Personal Reflection

Translation is perhaps the most intimate way of engaging with a text. During the translation process, one must dwell not only on the text itself—its progression, meaning, flow, style, and linguistic construction—but also deeply consider what the author has tried to convey. That message needs to come across. Perhaps my deep association with this text results from this complete immersion. The novel vividly reminds one of Márquez's Chronicle of a Death Foretold, especially in its long, fluid, lyrical sentences. But what has really stood out for me is the way women are portrayed in this text, especially Saptami. Each woman—Saptami, Rohini, even Jogeshwar's silent wife and Bireshwar's wife, Sadhana—faces subjugation. Still, they are sentient, agentic beings who claim their power and justice in their own ways, despite ruthless violence. It has been deeply satisfying, not only as a reader but also as a translator, to inhabit these women's experiences, especially when a male author portrays them authentically without attendant valorizations, which, in my observation, is rare.

Links:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/list/16528303.Sakyajit_Bhattacharya

Information related to the author of the novel

A statistician by profession, Sakyajit Bhattacharya has written seven novels, among which Shesh Mrito Pakhi is his most acclaimed, two short story anthologies, and a book of prose. Currently, he is working on a speculative fiction set around Kolkata. His novel The One Legged, translated from the Bengali by Rituparna Mukherjee, has been shortlisted for the JCB Prize for Literature 2024 and has won the Kala Literature Awards 2025.

Other translations by Rituparna Mukherjee (the author of this article):

- “The Monster’s House”, State of Matter Magazine, August 2024, https://stateofmatter.in/fiction/the-monsters-house/

- “The House with Wild Garden”, Hakara Journal, September 2024, https://www.hakara.in/sakyajit-bhattacharya-rituparna-mukherjee/

- “Extermination”, The Bombay Literary Magazine, December 2024, https://bombaylitmag.com/issue59-rituparna-mukherjee/

- “Oppressed” in Samovar-Stange Horizons, July 2025, http://samovar.strangehorizons.com/2025/07/28/oppressed-%e0%a6%86%e0%a6%95%e0%a7%8d%e0%a6%b0%e0%a6%be%e0%a6%a8%e0%a7%8d%e0%a6%a4/

- The One-Legged, Author: Sakyajit Bhattacharya, Translator: Rituparna Mukherjee, Source Language: Bengali, ISBN: 9788196395377, online link: https://amzn.eu/d/2F2JB2U

SPRING 2025 ISSUE

Welcome to the inaugural issue of SALIDmag (South Asian Languages, Images, and Data Magazine), published on March 21, 2025. SALIDmag will have one or more feature articles, book reviews, a spotlight article, and a reader's essay for novels in any South Asian language other than English. We hope you enjoy reading the first issue.

General Editor Sheenjini Ghosh and Book Review Editor Ragini Chakraborty are both graduate students of Comparative Literature. Feel free to write to them (scroll down the page for their emails) with comments on the current issue or about story ideas for the Fall 2025 issue.

FEATURE ARTICLE: Ragini Chakraborty in Conversation with Sumit Kumar

The South Asian Studies Initiative at CSAMES, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, hosted Sumit Kumar, a renowned award-winning graphic artist from India, for an evening of fun art-making and discussion on comics. The workshop, a collaboration with the International & Area Studies Library and the Spurlock Museum at UIUC, was held at the Collaboration and Community Gallery of Spurlock Museum on November 6, 2024.

‘From “Stories” to “Comics”: A Creative Rendezvous with Sumit Kumar’ was a workshop that brought together students from the university as well as the community members of Urbana-Champaign. With his ingenious wit and impeccable artistic skills, he held the attention of the workshop participants–consisting of faculty members, adults from the community, as well as kids alike.

He started the workshop by asking the participants a simple question: When was the last time you drew something, and why did you draw it? What seemed to be a simple question gathered various answers from across the room. Soon enough, everyone was sharing their emotions and their stories in connection with art. That stood out as the highlight of Kumar’s creative genius–how he turns stories into pictures or weaves stories through his illustrations. The workshop attendees got a brief insight into the world of the artist Sumit Kumar as he presented some of his work-in-progress, his animations that have received awards and recognition, the artworks that have been contributed by other artists or interns in his company –everything that features in his published website “BAKARMAX”.

Sumit Kumar studied engineering as an undergraduate but quickly went on to pursue his passion for making comics as he started as an intern at cartoonist Pran‘s studio. Since then, he has worked on several projects where he has created 3D simulations for the Indian Air Force, or written and illustrated stories with strong political sentiments and reference to historical and/or socio-cultural events. Along with pursuing stand-up comedy, he also became a part of a team that would go on to launch Comic Con India. His comics and webtoons are informed and shaped by his caste identity. Still, he does not believe that should be the only identity of his work (see here for Sumit Kumar’s response on his caste identity: https://deadant.co/it-helps-to-be-dumb-sumit-kumar-on-taking-on-big-projects-shark-tank-india-upcoming-adult-animated-series-aapki-poojita/) or anybody else who is narrating stories through their work.

On behalf of SALIDmag, Ragini Chakraborty had the following conversation with Sumit Kumar:

SALIDmag: Your focus has been making comics, primarily for adults in India. What do you think defines a contemporary Indian comic?

Sumit Kumar: Rather than define, I can draw out an average. Today, in India, comics are only made by extremely rich people who still call themselves middle class or, at best, upper-middle class. These are the top 15% of the country. Artists, despite the class they come from, are broke, and people in comics are too. Their stories show this disconnect or an approach that maybe a white person would take when telling a story of the “downtrodden” because a rich person in India is quasi-white. So most graphic novels are this - about some kind of social issue, very serious tonality, black and white, and boring. Even many children’s books are the same - a constant preaching of some sort. A lot of times, it's also an artist of repute trying to show how good an artist they are by making a book, which is a very badly done story. Fools are very confident; they believe they are breaking the world when, to be honest, they get to publish only because 85% of them are just trying to survive. In comparison, when you have to make something for a bigger audience, you have to be genuine and tell a really honest story. But it also has to engage very, very nicely. So, a contemporary Indian comic is a very boring thing, similar to contemporary Indian books. Comics were fantastic in the 90s; very vibrant adventures featuring superheroes and comedy. Obviously, there are fantastic exceptions - like Sudershan Chimpanzee by Rajesh Devraj and Meren Imchen and Karejwa by Varun Grover and Ankit Kapoor.

SALIDmag: Do you think of comics as a genre/medium that has different meaning depending on the context it is read in? Do you see graphic stories taught as a part of academia different from graphic works for the masses?

Sumit Kumar: It really depends on the comic. Take the case of a very commercial comic - Archies. None of us who read it in India knew what an American high school in the 60s looked like. We couldn't even believe that children in 11th and 12th could be this big and could own cars. And girls in the grade, or girls of any age in India - could wear swimsuits to beaches. But somehow after one comic, we accept that and read it - and from then on it's the story in that world. So, after that initial acceptance of the world, it didn't really matter much.

But then if we take the work of Joe Sacco - it feels so convenient. As someone sitting in India - I am fed up with white people telling other poor people dying stories. I mean, our death is documentary fodder, and despite Joe Sacco’s great work, it never felt great to me. So here, the context ruined everything. Still, when Guy Deslile does the same thing, I love it. Maybe it's him playing the idiot that helps.

I think all the regular publishing rules apply to comics, too. So yes, academic graphic novels could be different, but I have not seen one. Maybe I would use the Chrome Handbook that Scott McCloud made as an example. It's very boring for me to read but exciting for developers. But academicians are people too. and people can be interested in deep subjects without going to university - that’s where graphic novels like Logicomix are great.

The quickest thing people say when they see comics is: oh, it makes reading easy. It pisses me off, but it's true. The visuals do help. Yes I say then, use more and more comics in all levels of academics. But rather than just “explainers,” full-fledged original books should enter the curriculum. Because explainer comics can be boring at times. I would pick a Logicomix over the illustrated adaptation of Sapiens.

SALIDmag: Do you see comics as a tool that challenges linguistic barriers?

Sumit Kumar: When I went to Turkey, they had already made life easy by switching to Roman script for their language. I could read the words and Hindi and Turkish have a big overlap so there were so many common words that the country was accessible to me. But movies or books were still alien. But, Turkey’s comics industry is massive. They have comics newspapers - like Penguen. Opening that and reading it was so satisfying. Because quickly I could see so much of the world around me, from the locals' point of view, and I could understand many illustrations even when I did not understand all the words.

There are a lot of comics that have no words, but even with words, comics are far more accessible. My first comic book - Itch you can't scratch, uses Devanagari with English. But there are people who have zero Devanagari reading ability, and have just read the book using the visuals and the English bits.

SALIDmag: In this digital age of reels, shorts, and quick media consumption, how do you think the relevance of comics changes? Many creators illustrate folk tales and old fables of India, while others reproduce adaptations of 90s’ stories and TV shows as comics–where do you see your art standing amidst this?

Sumit Kumar: Of course, it affects, as it affects everything. Not everybody knows the behavior. Just look at your own behavior. But that in itself creates more space for comics. If TikTok is a snack, how many snacks can you eat? Eventually, you want a meal. That’s where films and comics come in. As for folktales and fables of India, those have always been the lowest-hanging fruit in comics and animation. It also makes sense from a financial point of view. India generally rushes to its culture and numbers when no other success is visible, so mythology, etc., is good business. As for nostalgia, it's another opium, sooo good. I personally don’t choose my stories on that basis as I serve one God, Humour. Is it funny? Can I make a fool out of myself while doing it? Will it induce giggles? Is it absurd or weird? Does it make people uncomfortable? These get me going.

As a consumer, I have stayed with books; so far, I have avoided reels. As a creator, since the last few years, my focus has been on animation, trying to find a balance between mass entertainment and well-made. And I often find myself serving no one. But in my survival as an artist and Bakarmax’s survival, maybe one day I will find that golden space where, as Conan says - “smart and stupid meet.”

SALIDmag: Do you think there is a specific South Asian identity when it comes to comics production?

Sumit Kumar: I haven't traveled the world that much, especially South Asia. I do believe that all colonial countries are the same. There are Macaulay’s children in all of them, and they form the upper class. Global-level decisions are made by white people who want certain things from certain people. It's like ok, terrorism - ok Pakistan, Afghanistan - you handle that. Ok, kids with malnutrition or girls with no sanitary pads - ok India, you do it, and so on. I think comics were outside of this when they were not literature and when they were stupid and dumb comic books. The day those books entered literature and became graphic novels–smart, serious–this segregation got into comics, too. But from time to time, some artists and creators defy these roles and make original comics. Our job should be to tell these stories - the identity can be accidental. But originality is the goal.

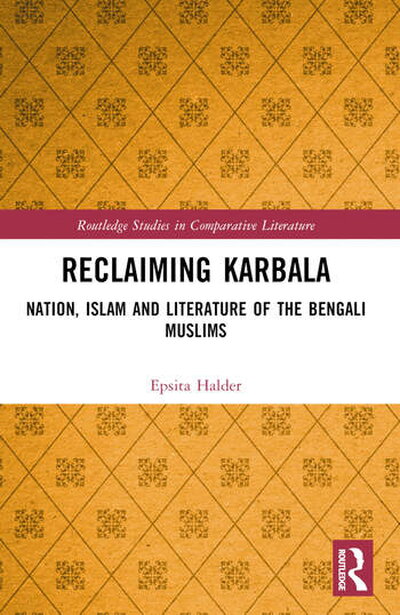

BOOK REVIEW: Aishi Bhattacharya reviews Epsita Halder's 'Reclaiming Karbala'

Reclaiming Karbala: Nation, Islam and Literature of the Bengali Muslims edited by Epsita Halder, Routledge, 2023, 346 pp, $56.99 (Paperback) ISBN 9781032195438.

Epsita Halder's book Reclaiming Karbala: Nation, Islam and Literature of the Bengali Muslims was honored at the 32nd World Book Award of the Islamic Republic of Iran. This recognition emphasizes its contribution towards cross-cultural dialogues among various approaches to Islamic studies. Karbala is a city in Iraq, historically significant as the site of the Battle of Karbala (680 CE), where Imam Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad, was martyred by the forces of the Umayyad caliph Yazid. This event is central to Shia Islam and is commemorated annually during Muharram, especially on Ashura, symbolizing resistance against tyranny. The book starts with Halder commenting on how the Karbala narrative—through Jarigan, Baul, and Fakir songs—has played a pivotal role in shaping Bengali Muslim identity. She highlights that literary translations and adaptations of Arabic-Persian sources have adapted Karbala-centric devotion into medieval Bangla literature since the sixteenth century. Marginalized communities on the fringes of both Islamic and Hindu society have reconstructed/ deconstructed Karbala again and again, weaving it into their own spiritual and anti-establishment narratives. By tracing its literary and cultural adaptations, Halder demonstrates that Karbala is a shared cultural memory transcending sectarian lines.

Halder also challenges the normative conception that Karbala is solely a Shi’a narrative. In chapter 5 of this book, she shows how Sunni and even non-Muslim communities in Bengal have engaged with the story, shaping it to fit their socio-political and cultural contexts. One of the book’s pivotal contributions is its examination of how Karbala has been utilized in nationalist rhetoric, particularly in the context of India and Bengal. In the conclusion, Halder argues that Karbala, instead of being a purely religious event, has served as a symbolic tool for expressing resistance against oppression—colonial rule, political subjugation, or social injustice. By highlighting how Karbala was narrated in diverse ways—sometimes as a universal struggle for justice, sometimes as a specifically Muslim experience—the book underscores the pluralistic and polyglot cultural, literary, and linguistic dimensions of South Asian Islamic practices.

In an era where sectarian and communal divisions are often emphasized, this historical perspective can offer a counterpoint to exclusivist narratives.

Contributor:

Aishi Bhattacharya is a graduate student in the Department of Comparative and World Literature.

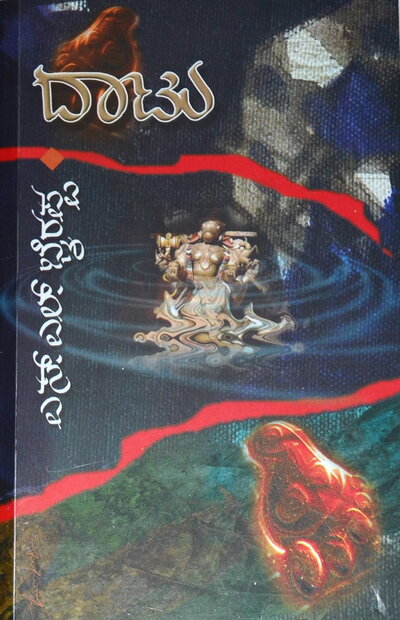

A NOVEL EXPERIENCE: Manjula Tekal on S. L. Bhyrappa's 'Daatu'

Introduction to the novel:

Dr. S. L. Bhyrappa’s Daatu stands out as a profound exploration of caste dynamics in rural Karnataka. Published in 1972, the novel delves deeply into the complex social structures of Indian society and its inherent pitfalls. Like most of Dr Bhyrappa’s works, it is a woman-centric novel narrated from the perspective of its protagonist, Satya, the daughter of a (Brahmin) priest at a historic temple. Satya is bold, free-thinking, and possesses an incisive mind. Raised by her single father, who adored her after her mother’s demise, she grew up surrounded by extraordinary love and encouragement, cultivating a questioning and analytical spirit. During college, she reconnects with Srinivasa, the son of a cunning local politician and minister. Their relationship is doomed from the outset due to deeply ingrained caste and class differences, as well as the attitudes of their families and relatives. The story builds toward a tragic climax as the toxic forces of caste and class politics inevitably drive the two young people apart. Srinivasa, a weak and indecisive character, quickly attaches himself to another woman, while Satya returns home to immerse herself in studying the history of the temple town.

The intricate workings of caste politics are meticulously examined against the backdrop of Satya’s relationships—with her family, friends, relatives, and, most importantly, her love interests. The author compels the readers to confront the psychological depths of the romantic relationships depicted in the novel, prompting them to reflect on their underlying complexities.

What makes Dr. Bhyrappa’s writing extraordinary is his restraint. He refrains from making explicit statements or offering conclusions, leaving no room for overt judgment. Instead, he places the narrative entirely in the hands of the reader, allowing them to draw their conclusions. His profound understanding of Indian history and philosophy enhances the reading experience.

Personal Statement:

I grew up immersed in Kannada literature, reading novels, short stories, long stories, biographies, and poetry. Even after decades of exploring various genres of English literature and embarking on my journey as a writer in English, I continue to hold several Kannada authors in the highest regard. I believe they are equal to, if not superior to, many so-called ‘world-class’ writers.

Enjoying a work of art requires two participants: the artist and the connoisseur. Genuine appreciation of art and literature often remains elusive without a deep cultural connection. Dr. S.L. Bhyrappa is one such luminary who speaks directly to the hearts and minds of his readers. His writing left an indelible mark on me during my formative years, and it has been my lifelong aspiration to emulate his brilliance as a writer.

Choosing a single work of his to discuss is no easy task, considering the remarkable volume of Bhyrappa’s critically acclaimed and hugely successful novels. My favorites include Vamshavriksha (The Family Tree), Grihabhanga (The Breaking of the Home), Bhitti (The Wall, his autobiography), Parva (Epoch), Uttarakanda, Daatu, Saartha, Avarana, and Mandra. I chose Daatu among these, as it stands out as a profound exploration of caste dynamics in rural Karnataka.

Contributor:

Manjula Tekal lives in Champaign. Her first novel, Devayani, was published in 2021.

SPOTLIGHT: Rohan Kapur's Course Scheduler

As the section title says, we focus on the achievements or skills of one or more students. Issue 1 spotlights Rohan Kapur, a rising Junior in Computer Engineering and a member of the Sanskrit research group at SALIDlab. Rohan created a course scheduler from scratch in his first semester. As the preregistration dates for Fall approach, all students are encouraged to check out the Course Scheduler at this link.

Here are some details about Rohan's project:

SALIDmag: How and when did you think about this?

Rohan: I started building the class scheduler during my first semester of freshman year after I had a really hard time putting together my own schedule. I actually ran the numbers and found out I had millions of possible schedule combinations—there was absolutely no way I could manually figure out the best one. That's when I realized I needed to build something to solve this problem, not just for me but for other students who were probably stuck in the same boat.

SALIDmag: What programming languages did you know at that time, and what new did you have to learn?

Rohan: At that point, I was already proficient in Python and JavaScript, but React.js was entirely new territory for me. This project provided the perfect opportunity to learn React while building something with practical utility. The frontend development aspect, particularly creating a coherent design system, was a significant challenge as it required design knowledge and skills I had avoided in previous projects.

SALIDmag: How much time did you spend on this?

Rohan: I spent a few weeks building and testing the site during my freshman fall semester, then shared it with some friends to get their feedback. Since then, I've been constantly updating it and adding new features every month. It's been really cool to see that the app has generated over 16,000 schedules for students on campus so far!

SALIDmag: And say a few lines about your involvement with the Sanskrit project.

Rohan: I've been working with Professor Rini Mehta and the SALIDlab team on developing NLP resources for Sanskrit for almost a year now. It's been a great experience that taught me a ton about natural language processing while letting me help preserve and analyze this ancient language.

SALIDmag Team

Sheenjini Ghosh, graduate student of Comparative and World Literature, is the general editor of SALIDmag for 2025-26.

She can be reached via email, at ghosh21@illinois.edu.

Ragini Chakraborty, a doctoral student of Comparative and World Literature, is the book review editor of SALIDmag for 2025-26.

She can be reached via email, at raginic2@illinois.edu.

Calls for Contributions

Call for contributions for "A Novel Experience"

For its second issue (Fallit 2025), SALID MAG invites 250-word essays for a curated section called "A Novel Experience."

Call for Entries: SALIDmag's 'A Novel Experience' collection aims to celebrate South Asian novels that offer unique insights into different cultural, historical, and social contexts. We welcome submissions highlighting novels from various regions, periods, and languages, emphasizing why these works deserve to be widely read and celebrated.

Who Can Submit?

- Undergraduate and graduate students from any discipline.

- Passionate readers who wish to share their recommendations with a broader audience.

Submission Guidelines

- Requirements:

- Title of the novel and author info.

- An essay on the novel (300-500 words), including its cultural and historical significance, AND a short reflection on your unique experience engaging with the novel. (100 –200 words).

- Language of the novel and whether an English translation is available.

- Eligibility:

- Novels can be in any South Asian language, but the essay must be written in English. Submissions should highlight novels that promote cultural understanding or present perspectives that are underrepresented in mainstream literature.

- Items to be submitted via the LINK:

- Title, Author, Original language in which it is written, Date of publication

- Essay on the novel's significance + A personal statement on the novel

- Links for the book (if available): Wikipedia, Goodread, Google Books, and Other links AND Links for the author: Wikipedia, Goodreads bio, etc.

- Deadline:

- Submit your proposals by March 15, 2025.

- How to Submit:

- Fill in the form available at this link.

Selected Entries: Selected submissions will be featured in the inaugural issue of SALIDmag (South Asian Languages, Images, and Data Magazine) on March 21, 2025.

Evaluation Criteria: Submissions will be evaluated based on the originality and depth of the recommendation, as well as the relevance of the novel to the theme of global and cross-cultural understanding.

Call for Reviews of Books on South Asia

We are looking for reviews of books on and related to South Asia in the broad field(s) of humanities and social sciences on topics ranging from history, culture, and literature to art, anthropology, gender studies, and digital humanities. These books should be works of scholarly criticism or research and should not be creative works such as novels, poems, plays, etc.

If you have come across a work that should be a part of a course module or should be recommended to scholars, please send us your suggestions through your reviews. Alternatively, if you would like to review a book but cannot decide which one to choose, you can send us your area(s) of interest and ask us for suggestions (email at raginic2@illinois.edu). We would be happy to send you options from our list. We are not currently sending copies to reviewers, so you should send suggestions for books that you have access to.